Shortly after the Sewol ferry sank in April, South Korean authorities hurriedly combed the messages and photos stored in the victims’ Kakao Talk chats to learn more about the tragic sinking.

One might wonder how such a probe was made possible, given that the victims were still missing. The fact was that Kakao Talk stores users’ private messages for about a week on its own server. Through a search warrant, the police could scrutinize private messages.

The implication is, if anything, unnerving. More than 90 percent of smartphone users here have installed Kakao Talk and continually share texts, photos and videos with their friends and family members, generating a massive amount of data vulnerable to being accessed by the authorities.

Uninstalling the app would not sufficiently protect one’s online privacy in this increasingly interconnected digital era.

People around the world continue to share their personal information via social media, and there is no sign of the trend reversing its course despite the growing concerns about online privacy.

One concern is that industry giants like Google and Facebook could use their huge databases for commercial and other purposes, while users have little clue about how their personal profiles and digital footprints are stored, handled and traded.

A prime example is the latest scandal that hit Facebook. The social media behemoth toyed with users’ emotions through an experiment without notifying its members. The company apologized, but its corporate image regarding its privacy policy suffered a setback, offering a glimpse of what could go wrong when big data is exploited.

But social media networks are only a part of the digital spectrum in which people share their own information willingly or unwittingly. Online marketers and data brokers gather a huge amount of personal data by tracking digital footprints, which are left behind as a result of Web browsing and stored in the form of cookies.

How much user information is being handled by data brokers and trackers? A ballpark figure was offered by investigative journalist Julia Angwin, who said in a feature in CBS’ “60 Minutes” news magazine that she tracked down 200-plus data brokers that held information on her and asked that it be deleted.

Worried about sneaky tracking tools hidden in websites, more online users are choosing specially designed Web browsers such as Tor, which offer online anonymity by bouncing Internet traffic around.

Offering a small relief to those concerned about online privacy, a European court recently ruled in favor of what it called “a digital right to be forgotten,” ordering Google to stop displaying links to certain personal information.

But this is not a simple issue, as critics argue the ruling would likely undermine the freedom of expression on the Internet and encourage censorship.

For tech-savvy South Koreans, the issue of online privacy is all the more vexing since much of their personal data has already been leaked to data brokers multiple times due to lax regulations, poor online security and rampant cyberattacks.

The pace of information sharing is expected to accelerate further as more life-changing services move online and more devices are interconnected through the Internet of Things. Data theft and personal information leaks might spin out of control as more people connect to the global digital repository.

Despite concerns, not many people would unplug their computers and throw out their smartphones. But it’s time to ponder what it means to share information on the Internet, and make a choice.

By Yang Sung-jin (insight@heraldcorp.com)

One might wonder how such a probe was made possible, given that the victims were still missing. The fact was that Kakao Talk stores users’ private messages for about a week on its own server. Through a search warrant, the police could scrutinize private messages.

The implication is, if anything, unnerving. More than 90 percent of smartphone users here have installed Kakao Talk and continually share texts, photos and videos with their friends and family members, generating a massive amount of data vulnerable to being accessed by the authorities.

Uninstalling the app would not sufficiently protect one’s online privacy in this increasingly interconnected digital era.

|

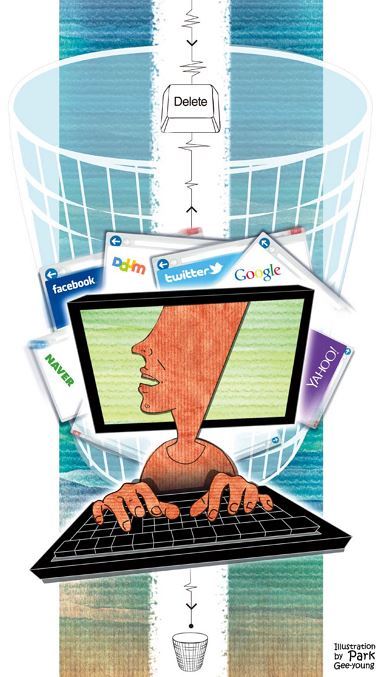

| (Illustration By Park Gee-young) |

People around the world continue to share their personal information via social media, and there is no sign of the trend reversing its course despite the growing concerns about online privacy.

One concern is that industry giants like Google and Facebook could use their huge databases for commercial and other purposes, while users have little clue about how their personal profiles and digital footprints are stored, handled and traded.

A prime example is the latest scandal that hit Facebook. The social media behemoth toyed with users’ emotions through an experiment without notifying its members. The company apologized, but its corporate image regarding its privacy policy suffered a setback, offering a glimpse of what could go wrong when big data is exploited.

But social media networks are only a part of the digital spectrum in which people share their own information willingly or unwittingly. Online marketers and data brokers gather a huge amount of personal data by tracking digital footprints, which are left behind as a result of Web browsing and stored in the form of cookies.

How much user information is being handled by data brokers and trackers? A ballpark figure was offered by investigative journalist Julia Angwin, who said in a feature in CBS’ “60 Minutes” news magazine that she tracked down 200-plus data brokers that held information on her and asked that it be deleted.

Worried about sneaky tracking tools hidden in websites, more online users are choosing specially designed Web browsers such as Tor, which offer online anonymity by bouncing Internet traffic around.

Offering a small relief to those concerned about online privacy, a European court recently ruled in favor of what it called “a digital right to be forgotten,” ordering Google to stop displaying links to certain personal information.

But this is not a simple issue, as critics argue the ruling would likely undermine the freedom of expression on the Internet and encourage censorship.

For tech-savvy South Koreans, the issue of online privacy is all the more vexing since much of their personal data has already been leaked to data brokers multiple times due to lax regulations, poor online security and rampant cyberattacks.

The pace of information sharing is expected to accelerate further as more life-changing services move online and more devices are interconnected through the Internet of Things. Data theft and personal information leaks might spin out of control as more people connect to the global digital repository.

Despite concerns, not many people would unplug their computers and throw out their smartphones. But it’s time to ponder what it means to share information on the Internet, and make a choice.

By Yang Sung-jin (insight@heraldcorp.com)

No comments:

Post a Comment