ATHENS (AP) ― Europe’s financial crisis eased as Greece installed a respected economist to replace its prime minister and Italy appeared poised to do the same ― both hoping that monetary experts can do better than the politicians who drove their nations so deeply into debt.

The announcement Thursday in Athens ― coupled with the prospect that volatile Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi will be ushered out soon ― quieted market fears, at least for now, that turmoil in Europe could threaten the global economy.

But significant challenges remain in both debt-heavy Mediterranean countries.

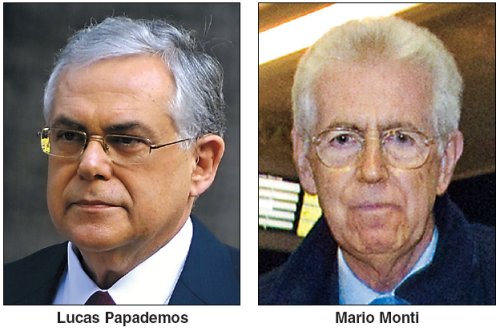

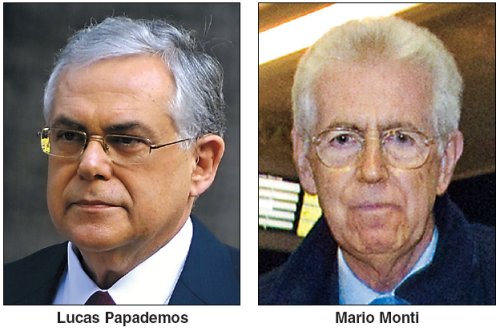

Greece’s new prime minister, Lucas Papademos, a former vice president of the European Central Bank, must quickly secure the crucial loan installment without which his country will go bankrupt before Christmas, and approve the EU’s $177 billion (130 billion euros) bailout deal.

In Italy, lawmakers have to pass new austerity measures over the next few days. However, expectations that respected economist Mario Monti will lead an interim technocratic government after Berlusconi goes helped lift the gloom.

Italy’s borrowing costs shot up alarmingly Wednesday to 7.4 percent on fears that Berlusconi would linger in office. But the markets calmed Thursday when it appeared that Italian lawmakers would approve the latest government austerity plans in the next few days and Berlusconi would resign after that.

Monti, 68, now heads Milan’s Bocconi University, but he made his reputation as the European Union competition commissioner who blocked General Electric’s takeover of Honeywell.

European stock markets rose on the twin Greek and Italian developments, while in the U.S. the Dow Jones industrial average was up 113 points, or 1 percent, a day after shedding nearly 400 points. The euro was also in demand, trading 0.5 percent higher at $1.3609.

Still, the European Union warned that the 17-nation eurozone could slip back into “a deep and prolonged” recession next year amid the debt crisis. The European Commission predicted the eurozone will grow a pallid 0.5 percent in 2012 ― much less than its earlier forecast of 1.8 percent. EU unemployment was forecast to be stuck at 9.5 percent.

Europe has already bailed out Greece, Portugal and Ireland ― but together they make up only about 6 percent of the eurozone’s economic output, in contrast to Italy’s 17 percent. Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest economy, is considered too big for Europe to bail out. It has a mountain of debt ― $2.6 trillion (1.9 trillion euros) ― and a substantial portion of that needs to be refinanced in the next few years.

In Greece, Papademos called for unity and promised to seek cross-party cooperation to keep Greece firmly in the 17-nation eurozone.

“The participation of our country in the eurozone is a guarantee for the country’s monetary stability. It is a driver of financial prosperity,” Papademos said after getting the mandate to form a Cabinet. “I am not a politician, but I have dedicated most of my professional life to exercising financial policy both in Greece and in Europe.”

The 64-year-old Papademos, who also served as Bank of Greece governor, will lead a government backed by both Greece’s governing Socialists and the opposition conservatives until early elections, tentatively set for February. He replaces outgoing Prime Minister George Papandreou midway through his four-year term, ending a family dynasty that has dominated Greek politics for decades.

In Washington, State Department spokesman Mark Toner welcomed Papademos’ appointment and “the consensus that’s been reached in Greece over the need to implement the country’s reform commitments to the IMF as well as the European Union.”

The new Greek cabinet will be sworn in Friday. There has been no announcement on its composition, and officials said negotiations continued late Thursday.

However, two government officials and two opposition lawmakers, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the issue, said Evangelos Venizelos was expected to remain finance minister. Venizelos was deeply involved in negotiating the European rescue plan.

Greek analyst Platon Monokroussos said hopes have been raised that the new prime minister will help the country regain its lost international credibility.

“Of course, the new government will fight an uphill battle to implement a very austere adjustment program in Greece, very significant structural reforms, and this creates a lot of challenges,” said Monokroussos, who heads financial market research at Eurobank. “But overall, today’s outcome is positive.”

European officials greeted the Greek news with relief.

“The agreement to form a government of national unity opens a new chapter for Greece,” said a joint statement by European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso and European Council President Herman Van Rompuy.

They stressed that “it is important for Greece’s new government to send a strong cross-party message of reassurance to its European partners that it is committed to doing what it takes to set its debt on a steady downward path.”

The interim government’s mandate includes passing the $177 billion (130 billion euros) European debt deal that took months to work out, and ensuring the country receives the next $11 billion (8 billion euros) installment of its initial 110 billion euros bailout.

Under the new deal, private bondholders will forgive 50 percent ― or some 100 billion euros ― of their Greek debt holdings.

Eurozone officials are withholding the next loan installment until Athens formally approves the rescue package. They have also demanded a written pledge from Papademos, Papandreou, opposition party leader Antonis Samaras, the head of Greece’s central bank and the finance minister.

Many Greeks are angry after 20 months of government austerity measures, including repeated salary and pension cuts and tax hikes to meet the conditions of the country’s first bailout. Despite the belt-tightening, the Socialist government repeatedly missed its financial targets as Greece fell into a deep recession, amid rapidly rising unemployment that surged to 18.4 percent in August ― close to double the EU average.

Papademos’ appointment followed 10 days of political turmoil triggered by Papandreou’s shock announcement that he wanted to put the latest European bailout deal to a referendum. Fears that the agreement would be defeated led to mayhem on international markets and angered both European leaders and his own Socialist lawmakers.

Bowing to pressure, Papandreou agreed to resign and reached a historic power-sharing deal with Samaras on Sunday to form a transitional government.

Papademos, who is not a member of any party, has been operating lately as an adviser to the prime minister.

He taught at Columbia University and worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston before returning to Greece, where he headed the central bank from 1994 to 2002 after helping fend off a speculative attack on the drachma, Greece’s pre-euro currency.

At the Bank of Greece’s helm, Papademos presided over an era of increasing independence from the government that was crucial in helping Greece secure membership in the eurozone. He then spent eight years at the European Central Bank.

The announcement Thursday in Athens ― coupled with the prospect that volatile Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi will be ushered out soon ― quieted market fears, at least for now, that turmoil in Europe could threaten the global economy.

But significant challenges remain in both debt-heavy Mediterranean countries.

Greece’s new prime minister, Lucas Papademos, a former vice president of the European Central Bank, must quickly secure the crucial loan installment without which his country will go bankrupt before Christmas, and approve the EU’s $177 billion (130 billion euros) bailout deal.

In Italy, lawmakers have to pass new austerity measures over the next few days. However, expectations that respected economist Mario Monti will lead an interim technocratic government after Berlusconi goes helped lift the gloom.

Italy’s borrowing costs shot up alarmingly Wednesday to 7.4 percent on fears that Berlusconi would linger in office. But the markets calmed Thursday when it appeared that Italian lawmakers would approve the latest government austerity plans in the next few days and Berlusconi would resign after that.

Monti, 68, now heads Milan’s Bocconi University, but he made his reputation as the European Union competition commissioner who blocked General Electric’s takeover of Honeywell.

European stock markets rose on the twin Greek and Italian developments, while in the U.S. the Dow Jones industrial average was up 113 points, or 1 percent, a day after shedding nearly 400 points. The euro was also in demand, trading 0.5 percent higher at $1.3609.

Still, the European Union warned that the 17-nation eurozone could slip back into “a deep and prolonged” recession next year amid the debt crisis. The European Commission predicted the eurozone will grow a pallid 0.5 percent in 2012 ― much less than its earlier forecast of 1.8 percent. EU unemployment was forecast to be stuck at 9.5 percent.

Europe has already bailed out Greece, Portugal and Ireland ― but together they make up only about 6 percent of the eurozone’s economic output, in contrast to Italy’s 17 percent. Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest economy, is considered too big for Europe to bail out. It has a mountain of debt ― $2.6 trillion (1.9 trillion euros) ― and a substantial portion of that needs to be refinanced in the next few years.

In Greece, Papademos called for unity and promised to seek cross-party cooperation to keep Greece firmly in the 17-nation eurozone.

“The participation of our country in the eurozone is a guarantee for the country’s monetary stability. It is a driver of financial prosperity,” Papademos said after getting the mandate to form a Cabinet. “I am not a politician, but I have dedicated most of my professional life to exercising financial policy both in Greece and in Europe.”

The 64-year-old Papademos, who also served as Bank of Greece governor, will lead a government backed by both Greece’s governing Socialists and the opposition conservatives until early elections, tentatively set for February. He replaces outgoing Prime Minister George Papandreou midway through his four-year term, ending a family dynasty that has dominated Greek politics for decades.

In Washington, State Department spokesman Mark Toner welcomed Papademos’ appointment and “the consensus that’s been reached in Greece over the need to implement the country’s reform commitments to the IMF as well as the European Union.”

The new Greek cabinet will be sworn in Friday. There has been no announcement on its composition, and officials said negotiations continued late Thursday.

However, two government officials and two opposition lawmakers, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the issue, said Evangelos Venizelos was expected to remain finance minister. Venizelos was deeply involved in negotiating the European rescue plan.

Greek analyst Platon Monokroussos said hopes have been raised that the new prime minister will help the country regain its lost international credibility.

“Of course, the new government will fight an uphill battle to implement a very austere adjustment program in Greece, very significant structural reforms, and this creates a lot of challenges,” said Monokroussos, who heads financial market research at Eurobank. “But overall, today’s outcome is positive.”

European officials greeted the Greek news with relief.

“The agreement to form a government of national unity opens a new chapter for Greece,” said a joint statement by European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso and European Council President Herman Van Rompuy.

They stressed that “it is important for Greece’s new government to send a strong cross-party message of reassurance to its European partners that it is committed to doing what it takes to set its debt on a steady downward path.”

The interim government’s mandate includes passing the $177 billion (130 billion euros) European debt deal that took months to work out, and ensuring the country receives the next $11 billion (8 billion euros) installment of its initial 110 billion euros bailout.

Under the new deal, private bondholders will forgive 50 percent ― or some 100 billion euros ― of their Greek debt holdings.

Eurozone officials are withholding the next loan installment until Athens formally approves the rescue package. They have also demanded a written pledge from Papademos, Papandreou, opposition party leader Antonis Samaras, the head of Greece’s central bank and the finance minister.

Many Greeks are angry after 20 months of government austerity measures, including repeated salary and pension cuts and tax hikes to meet the conditions of the country’s first bailout. Despite the belt-tightening, the Socialist government repeatedly missed its financial targets as Greece fell into a deep recession, amid rapidly rising unemployment that surged to 18.4 percent in August ― close to double the EU average.

Papademos’ appointment followed 10 days of political turmoil triggered by Papandreou’s shock announcement that he wanted to put the latest European bailout deal to a referendum. Fears that the agreement would be defeated led to mayhem on international markets and angered both European leaders and his own Socialist lawmakers.

Bowing to pressure, Papandreou agreed to resign and reached a historic power-sharing deal with Samaras on Sunday to form a transitional government.

Papademos, who is not a member of any party, has been operating lately as an adviser to the prime minister.

He taught at Columbia University and worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston before returning to Greece, where he headed the central bank from 1994 to 2002 after helping fend off a speculative attack on the drachma, Greece’s pre-euro currency.

At the Bank of Greece’s helm, Papademos presided over an era of increasing independence from the government that was crucial in helping Greece secure membership in the eurozone. He then spent eight years at the European Central Bank.

No comments:

Post a Comment